Circular Design in London: A Practical Strategy for Reducing Embodied Carbon

Circular Design in London: Why It Is Gaining Momentum

Circular design in London is becoming one of the most useful ways to connect sustainability with real project decisions. It brings embodied carbon into the same conversation as design quality, programme, and long-term asset performance, because it focuses on what is already there and what the project is choosing to add, replace, or discard.

At its simplest, circular design is about keeping materials at their highest value for as long as possible. That can mean retaining a structural frame, upgrading a façade in layers rather than replacing it wholesale, salvaging and reusing components, or designing new elements so they can be repaired, upgraded, and disassembled later. It is sustainability, but it is also design craft. It changes the set of options available to a team and often leads to buildings that are more adaptable and more distinctive.

Why Circular Design Reduces Embodied Carbon in Construction

Embodied carbon covers emissions from product manufacture and construction, and depending on the assessment boundary may also include repair, replacement and end of life impacts. Circular design reduces that impact by avoiding unnecessary new manufacture and by limiting premature replacement cycles that create repeat carbon and repeat waste.

This is where circularity is most practical. It does not ask teams to “do everything differently.” It asks teams to be more intentional about intervention, keeping value where it exists and upgrading only where it is needed to meet performance, safety, and usability goals.

Circular Design is a Project Strategy, Not a Product Choice

Circular design gives teams an alternative to defaulting to replacement as the main path to performance. The early questions sharpen what we can keep and improve, what truly needs to change, and where can performance be lifted through targeted intervention rather than a full reset.

The benefit isn’t only carbon reduction. It also tends to produce stronger design outcomes because retention and reuse bring real material character, proportion, and texture into a project. You are working with value that already exists, not trying to recreate it later.

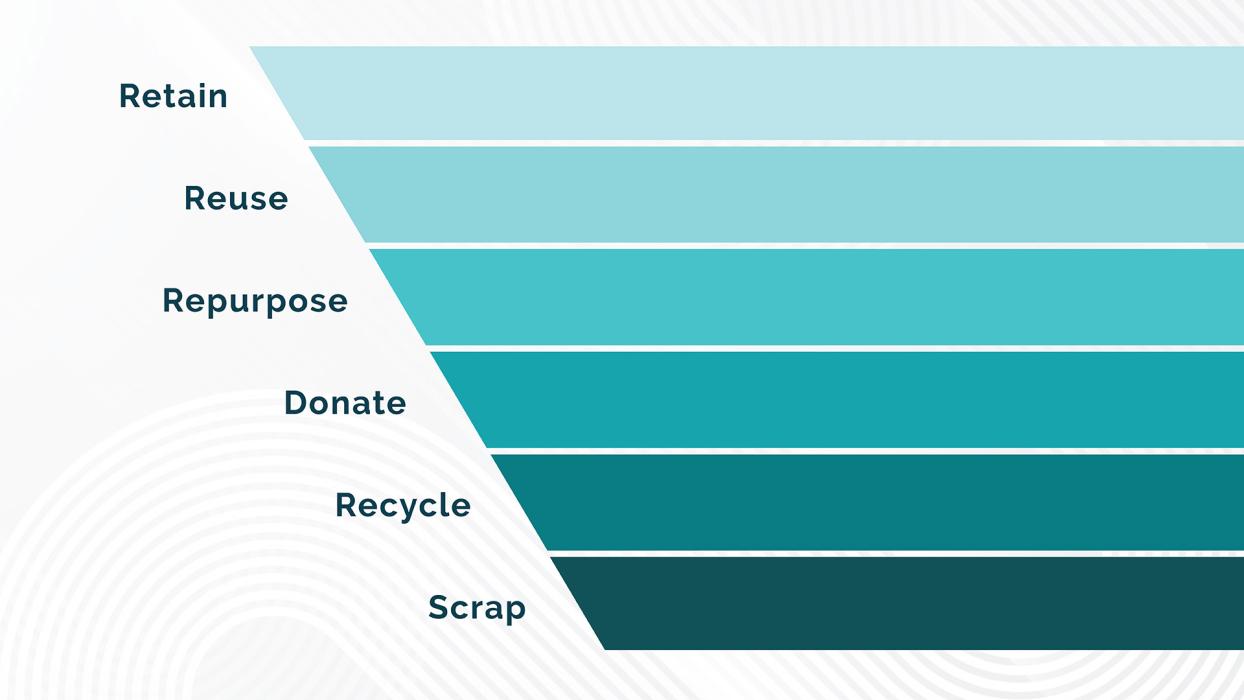

The Circular Hierarchy in Construction: Retain, Reuse, Recycle

Circular design isn’t a binary choice between “reused” and “new.” It is a hierarchy of value that helps teams act quickly without getting stuck. The highest-value outcome is to retain: keep what works, strengthen or adapt only where needed. Next comes reuse and future reuse: keep materials in use with minimal reprocessing, whether on-site or elsewhere. When direct reuse isn’t feasible, materials can be donated to extend their useful life beyond the project. Only later do you get to recycling, which can still be useful, but usually retains less value and requires more processing than true reuse. Put simply, circularity keeps material value in play instead of writing it off as waste.

Where Circular Design Has the Greatest Impact: Structure, Façade, and Building Services

Circular outcomes tend to be decided where sustainability and design are inseparable.

Structure is often the biggest opportunity because it holds so much embodied value and sets flexibility. Retaining or adapting a frame can be one of the most meaningful embodied carbon moves a project makes, but it is also a design decision. It shapes spans, heights, proportions, and how easily a building can change use without being rebuilt.

Façades are where circularity becomes both technical and visible. The envelope shapes comfort, energy demand, and user experience, but it also sets the future intervention cycle. A façade conceived as a layered, maintainable system makes it possible to upgrade performance over time without defaulting to wholesale replacement. That is good sustainability and good asset planning.

Building services and fit-out are often where circularity becomes practical fastest, because these elements change more frequently. Designing for access, demountability, and targeted upgrades reduces disruption, reduces waste, and keeps the building easier to adapt.

Services are also increasingly part of the reuse conversation, through retention of viable plant and distribution where possible, and designing upgrades as targeted interventions rather than full strip out.

Overall, circular design is a way of making sustainability tangible. It turns embodied carbon into early, buildable decisions, while also supporting adaptability and design quality. In London, that combination is why circularity is gaining momentum: it helps teams avoid unnecessary replacement, keep material value in play, and deliver assets that can evolve rather than reset.